Food is one of the oldest and most fundamental aspects of human civilization. The way our ancestors ate tells us who they were, how they lived, and what resources were available to them. Some of the earliest known recipes were recorded on clay tablets, tomb walls, or passed down through generations in archaeological findings.

Below, we explore five of the world’s oldest recorded recipes, their historical sources, and how you can make them today using modern adaptations.

1. Mesopotamian Stew (c. 1730 BCE) – The World’s Oldest Recorded Recipe

Origin & Source

- Civilization: Ancient Mesopotamia

- Source: Yale Culinary Tablets (YBC 4644, YBC 8958, YBC 4648)

- Date: c. 1730 BCE

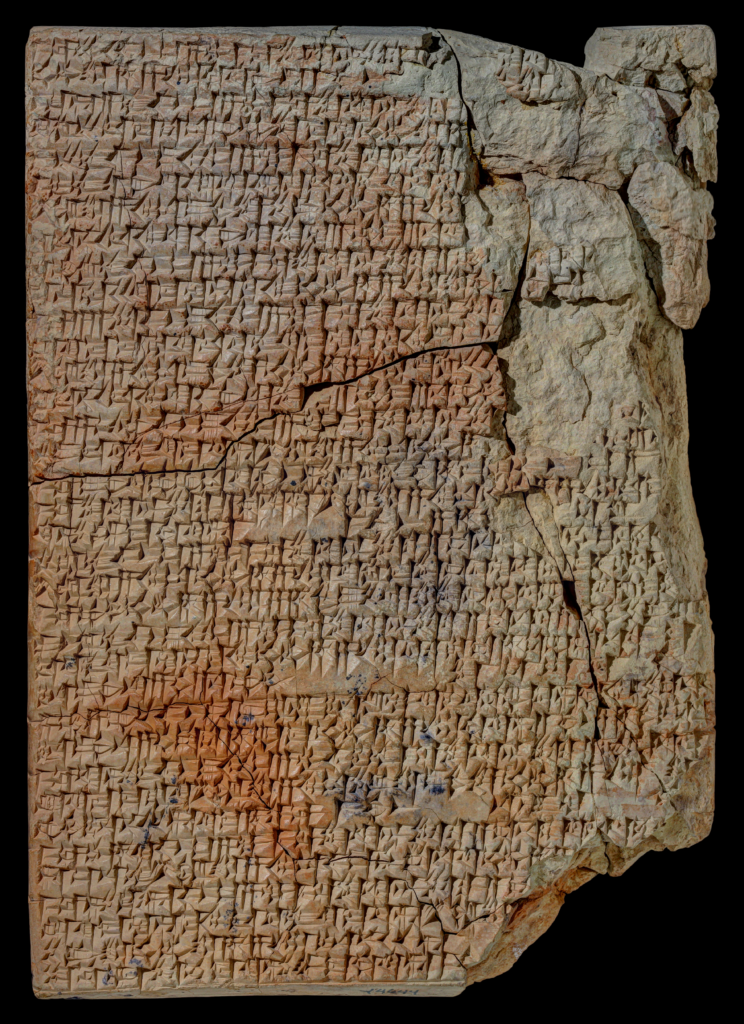

The oldest recorded recipe in human history comes from the Yale Culinary Tablets, a collection of cuneiform inscriptions from ancient Mesopotamia, dated to approximately 1730 BCE. These clay tablets, written in Akkadian, contain detailed instructions for preparing various stews, proving that the people of Mesopotamia had an advanced understanding of cooking. The recipes describe ingredients such as lamb, onions, garlic, leeks, and barley, which were combined with spices and herbs to create complex, flavorful dishes.

Stews were an essential part of the Mesopotamian diet, particularly for the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. With rich farmlands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Mesopotamians had access to a diverse range of ingredients, including lentils, chickpeas, dates, and dairy products. These stews were likely cooked in clay pots over open fires, slowly simmered to develop deep flavors, much like modern Middle Eastern stews. The presence of barley flour in the recipes suggests that they were often served with flatbreads or barley cakes, making them a complete and hearty meal.

What makes these tablets remarkable is their level of culinary sophistication. Unlike simple lists of ingredients found in other ancient texts, these recipes include instructions for preparation and cooking techniques, showing that Mesopotamian cooks understood how to balance flavors. Some of the tablets even specify the order in which ingredients should be added, an early example of structured recipe writing. This suggests that cooking was a refined skill, possibly reserved for temple kitchens, royal courts, or wealthy households.

How to Make It (Modern Adaptation)

Ingredients:

- 1 lb lamb shoulder, cut into chunks

- 1 tbsp olive oil (or animal fat for authenticity)

- 1 large onion, chopped

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- ½ cup leeks, chopped

- ½ tsp coriander

- ½ tsp cumin

- 2 tbsp barley flour (or wheat flour)

- 2 cups water or broth

- Salt to taste

Instructions:

- Sear the lamb in oil until browned.

- Add onions, garlic, and leeks, cooking until softened.

- Sprinkle coriander, cumin, and barley flour over the mixture and stir.

- Pour in water or broth, reduce heat, and simmer for 1.5 hours until tender.

- Serve with barley flatbread, as the Mesopotamians did.

Want to learn more about Mesopotamia? 📖 Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others (Oxford World’s Classics)

2. Nettle Pudding (c. 6000 BCE) – The Oldest Known Recipe from Britain

Origin & Source

- Civilization: Ancient Britain

- Source: Archaeological findings in the UK

- Date: c. 6000 BCE

Nettle pudding is one of the oldest known recipes in the world, dating back to around 6000 BCE in prehistoric Britain. This dish, made from wild nettles and other foraged greens, showcases how early hunter-gatherer societies relied on their natural environment to survive. Before the advent of agriculture, people in ancient Britain lived off the land, collecting edible plants, nuts, and roots, while supplementing their diet with fish and small game.

Archaeological discoveries in Britain’s Mesolithic and Neolithic sites suggest that nettles, sorrel, dandelion, and watercress were among the most commonly gathered plants. These greens were high in vitamins and minerals, making them a crucial part of the diet, especially after long winters when fresh food was scarce. The idea of boiling or steaming nettles into a thick, porridge-like dish reflects the rudimentary cooking methods available at the time. Early Britons likely wrapped the mixture in large leaves like burdock or cabbage, then steamed it over a fire or in clay pots.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this dish is its use of nettles, a plant often considered a nuisance today due to its painful sting. However, nettles were widely used in prehistoric Britain, not just for food but also for medicine and fabric production. When cooked, nettles lose their sting, becoming a nutritious and flavorful ingredient rich in iron, calcium, and vitamin C. They were particularly valuable in the spring, when they were among the first greens to emerge after winter.

How to Make It (Modern Adaptation)

Ingredients:

- 2 cups young nettle leaves (handle with gloves)

- 1 cup mixed wild greens (dandelion, sorrel, etc.)

- 1 cup barley or wheat flour

- 1 tsp salt

- Water, as needed

Instructions:

- Blanch nettles in boiling water for 1-2 minutes to remove the sting, then chop finely.

- Mix nettles, wild greens, flour, and salt into a thick batter.

- Wrap in leaves (like cabbage or grape leaves) and steam for 30 minutes.

- Serve warm, optionally with honey or butter.

Want to learn more? 📖 Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland Before the Romans

3. Ancient Egyptian Bread (c. 1500 BCE) – The Bread of the Pharaohs

Origin & Source

- Civilization: Ancient Egypt

- Source: Tomb paintings & archaeological findings

- Date: c. 1500 BCE

Bread was the lifeblood of ancient Egyptian civilization, serving as a dietary staple for both pharaohs and laborers alike. Archaeological evidence, including tomb paintings, preserved bread loaves, and written records, reveals that bread-making was a central part of daily life in Egypt as early as 1500 BCE. More than just a source of sustenance, bread was also used in religious rituals, as offerings to the gods, and even as currency for workers building the grand pyramids.

Unlike modern bread, ancient Egyptian bread was made primarily from emmer wheat and barley, two of the earliest cultivated grains in human history. Emmer wheat, also known as farro, was difficult to process due to its tough husks, requiring labor-intensive threshing and grinding. The Egyptians ground their grains using stone mills, creating a coarse, gritty flour that often contained bits of stone—so much so that dental analysis of Egyptian mummies frequently shows severe tooth wear from lifelong consumption of bread with embedded grit.

Bread in ancient Egypt came in many shapes and sizes, from flatbreads and small round loaves to more elaborate forms resembling animals and deities. The loaves were often fermented naturally using wild yeasts, producing a slightly sour, dense bread. These breads were typically baked in clay ovens or on hot stones, giving them a rustic texture and a unique, slightly smoky flavor.

Egyptian bread-making was an advanced and widespread craft, and many households had their own bread ovens and grinding stones. However, large-scale bread production also took place in temple bakeries and royal kitchens, where workers produced enormous quantities of bread daily. These bakeries used a two-stage baking method, where dough was first shaped into loaves and partially baked, then placed in conical bread molds and finished in large communal ovens.

How to Make It (Modern Adaptation)

Ingredients:

- 3 cups emmer wheat flour (or whole wheat)

- 1½ tsp salt

- 1 tsp active dry yeast

- 1½ cups warm water

Instructions:

- Dissolve yeast in warm water and let sit for 10 minutes until frothy.

- Mix flour and salt in a bowl, then add the yeast mixture.

- Knead into a soft dough and let rise for 2 hours.

- Shape into small loaves and bake at 375°F (190°C) for 30 minutes.

Want to learn more? The Pharaoh’s Kitchen: Recipes from Ancient Egypts Enduring Food Traditions

4. Chinese Millet Noodles (c. 2000 BCE) – The Oldest Pasta

Origin & Source

- Civilization: Ancient China

- Source: Lajia Archaeological Site

- Date: c. 2000 BCE

In 2005, archaeologists unearthed a 4,000-year-old bowl of noodles at the Lajia site in China, making it the oldest known example of pasta. This discovery revolutionized our understanding of the origins of noodles, proving that they were being made and eaten in China long before pasta became a staple in Italy or the Middle East. The noodles, remarkably well-preserved, were made from millet, rather than wheat, highlighting the early agricultural practices of ancient China.

During the Neolithic period (c. 2000 BCE), millet was one of the most widely cultivated grains in northern China. Unlike wheat or rice, millet grows well in dry, arid climates, making it a staple grain for early Chinese civilizations. Ancient Chinese farmers ground millet into flour, which was then mixed with water to create dough. This dough was hand-pulled or cut into long, thin strands, much like modern la mian (hand-pulled noodles). The discovery at Lajia suggests that the Chinese had already developed a sophisticated noodle-making technique, predating the first written records of pasta by thousands of years.

The Lajia site itself is significant for more than just its noodles. Often called “China’s Pompeii”, Lajia was an ancient settlement that was suddenly abandoned following a catastrophic earthquake and flood. The noodles, sealed in an inverted clay bowl, were preserved under layers of sediment, preventing decomposition. This unique preservation allowed researchers to study the structure and composition of the noodles, confirming that they were made from millet, a grain still widely used in Chinese cuisine today.

Noodles have played an essential role in Chinese culture, cuisine, and symbolism for millennia. They are often associated with longevity, prosperity, and good fortune, particularly during festivals and celebrations. This cultural significance dates back thousands of years, showing how deeply ingrained noodles are in the Chinese culinary tradition.

How to Make It (Millet-Based Version)

Ingredients:

- 2 cups millet flour

- ½ cup warm water

- Pinch of salt

Instructions:

- Mix flour and water into a dough, knead well, and let rest for 30 minutes.

- Roll the dough into thin ropes and hand-pull into noodles.

- Boil in salted water for 2-3 minutes.

- Serve with a light soy-based broth or sesame sauce.

5. Sumerian Beer (c. 3000 BCE) – The Oldest Fermented Recipe

Origin & Source

- Civilization: Ancient Sumer (Mesopotamia)

- Source: Hymn to Ninkasi (an ancient Sumerian poem dedicated to the goddess of brewing)

- Date: c. 3000 BCE

Beer is one of the oldest alcoholic beverages in human history, and its origins date back to ancient Sumer in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). The earliest records of brewing come from around 3000 BCE, when the Sumerians developed an advanced brewing process using barley, water, and fermentation techniques that would become the foundation of beer-making for millennia.

The primary source for Sumerian brewing knowledge comes from the Hymn to Ninkasi, a poem dedicated to Ninkasi, the goddess of beer and brewing. This hymn, written in cuneiform on clay tablets, not only praises the goddess but also describes the brewing process in detail, making it one of the earliest recorded recipes in history. The text highlights how beer was made using bappir (barley bread), malted grains, and water, which were left to ferment in clay vats under the sun. The result was a thick, cloudy, and slightly sour beer, vastly different from the crisp lagers and ales we drink today.

Beer was not just a popular beverage in ancient Sumer; it was a staple of daily life. Workers, including those who helped build temples and ziggurats, were often paid in beer and bread, reinforcing its role as a nutritional necessity rather than just a luxury. The Sumerians consumed beer with reed straws, as fermentation byproducts often left a layer of sediment at the bottom of clay drinking vessels. This practice can be seen in ancient artwork, where Sumerians are depicted drinking from large communal pots using straws.

Beer also played a significant role in Sumerian religion and social gatherings. It was commonly offered to the gods, served at banquets, and used in ceremonial rituals. The brewing industry was largely female-dominated, with priestesses of Ninkasi overseeing much of the beer production. This underscores how brewing was not just a domestic task but also a spiritual and communal practice.

How to Make It (Modern Adaptation)

Ingredients:

- 2 lbs barley malt (or crushed barley)

- 1 loaf unsweetened barley bread (crumbled)

- 1 gallon water

- ½ cup honey

- 1 packet brewer’s yeast

Instructions:

- Mash barley bread & malt in warm water, letting it soak overnight.

- Strain out solids, leaving behind the liquid.

- Add honey and yeast, letting it ferment for 5-7 days.

- Strain & bottle, then let sit for another few days before drinking.

- Enjoy your ancient-style beer—likely cloudy, slightly sour, and naturally carbonated.

Want to learn more? Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food

Five Historic & Iconic Recipes

These five ancient recipes provide a rare glimpse into the culinary traditions of some of the earliest civilizations on Earth. From the slow-simmered Mesopotamian stew to the hand-pulled millet noodles of ancient China, these dishes reveal the resourcefulness, creativity, and cultural significance of food throughout history. Each meal was more than just sustenance—it was deeply woven into religion, society, and daily life, shaping the way people gathered, celebrated, and survived.

What’s truly remarkable is how many of these techniques have endured for thousands of years. The fermentation process used for Sumerian beer, the natural leavening of Egyptian bread, and the communal meals of Mesopotamian kitchens all have modern counterparts today. Even though ingredients and cooking methods have evolved, these ancient recipes remind us that our connection to food is timeless.

By recreating these dishes in our own kitchens, we’re not just eating history—we’re experiencing the flavors, traditions, and stories of those who lived thousands of years before us. Whether you’re brewing beer like a Sumerian priestess, hand-pulling noodles like an ancient Chinese cook, or baking bread fit for a pharaoh, these recipes allow us to step back in time and honor the culinary legacy of our ancestors.