The rich history of Ireland is a tapestry woven with tales of struggle, resilience, and a deep connection to the land. Among the many symbols of Irish heritage, food plays a crucial role in telling the story of the people and their journey through history.

One such dish is Colcannon, a humble yet beloved Irish dish made from mashed potatoes, cabbage or kale, and butter. While it’s enjoyed today as a comfort food, Colcannon has roots that reach back to a time of revolution and upheaval in Ireland.

This episode of Revolutionary Recipes explores the connection between Colcannon and the Irish Revolution, shedding light on how this simple dish became a symbol of sustenance and survival during a pivotal moment in Irish history.

The Irish War of Independence

Origins and Prelude to War

The Irish War of Independence, also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war that took place from 1919 to 1921 between the forces of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British Crown forces, including the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), the British Army, and the notorious Black and Tans. The conflict arose from the long-standing tension between the Irish desire for self-governance and British control over the island.

The war was sparked by the growing momentum for Irish independence following the Easter Rising of 1916, a rebellion that, although crushed, ignited a fervent nationalist movement. The execution of the Rising’s leaders by the British authorities galvanized public opinion in Ireland, leading to a surge in support for the Sinn Féin party, which championed the cause of complete independence.

In the 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won a sweeping victory, securing 73 of Ireland’s 105 parliamentary seats. Instead of taking their seats in the British Parliament, Sinn Féin’s elected representatives formed their own parliament, Dáil Éireann, in January 1919, and declared an independent Irish Republic.

The Outbreak of War

The war began on January 21, 1919, the same day the Dáil first met, when a group of IRA volunteers ambushed a convoy of the RIC in Soloheadbeg, County Tipperary, killing two officers. This marked the beginning of widespread guerrilla warfare across Ireland.

The IRA, under the leadership of figures like Michael Collins and Éamon de Valera, conducted a campaign of ambushes, raids, and assassinations aimed at undermining British authority and forcing them to withdraw from Ireland.

The British responded with a harsh counter-insurgency campaign, deploying additional troops and recruiting the Black and Tans, a force of ex-soldiers infamous for their brutal tactics against civilians suspected of supporting the IRA.

Despite their superior numbers and resources, the British forces struggled to suppress the IRA, who used their knowledge of the local terrain and widespread popular support to carry out effective hit-and-run attacks.

The Stalemate and Path to Negotiations

The war took a heavy toll on both sides, with significant loss of life and widespread destruction. Civilians often found themselves caught in the crossfire, and the British reprisals against suspected IRA sympathizers led to increased support for the independence movement.

By mid-1921, the conflict had reached a stalemate, with neither side able to secure a decisive victory. Recognizing the futility of continued fighting, both the British government and the leaders of Sinn Féin sought a political solution.

This led to a truce in July 1921, followed by negotiations that culminated in the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. The treaty established the Irish Free State as a self-governing dominion within the British Commonwealth, effectively ending the war, though it also led to the Irish Civil War as factions within the independence movement split over the terms of the agreement.

Legacy of the War

The Irish War of Independence was a pivotal moment in Irish history, marking the end of centuries of British rule over most of the island and the beginning of Ireland’s journey toward full sovereignty. The struggle and sacrifices made during the war left a lasting impact on the Irish national consciousness, and the era remains a significant chapter in the story of Ireland’s quest for self-determination.

Colcannon’s Connection to the Irish Revolution

Colcannon, with its roots in the Irish countryside, is more than just a dish; it is a symbol of the Irish connection to the land and the sustenance it provided during times of hardship. During the Irish Revolution, food was often scarce, and the simple ingredients that made up Colcannon—potatoes, cabbage or kale, and butter—were among the few staples that remained accessible to the rural poor.

The dish itself embodies the resilience of the Irish people, who have long relied on the land to sustain them through famine, conflict, and oppression. Potatoes, the main ingredient in Colcannon, have been a dietary staple in Ireland since the 17th century, but they are also a reminder of the Great Famine of the 1840s, when blight devastated the potato crop and led to mass starvation. Despite this tragic history, the potato remained central to the Irish diet, and Colcannon became a way to stretch limited resources into a nourishing meal.

During the revolution, as the Irish fought for their independence, Colcannon was a dish that many families could turn to for comfort and sustenance. It was a way to make the most of what little they had, and its hearty, warming nature provided solace in a time of uncertainty and fear. For the Irish rebels and their families, Colcannon was a connection to their heritage and a symbol of the enduring spirit that would ultimately lead to the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922.

The Dish Explained: Colcannon

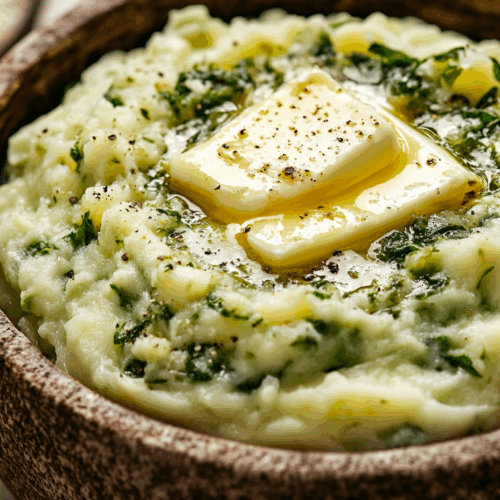

Colcannon is a simple, yet flavorful dish that has been a part of Irish cuisine for centuries. It is traditionally made with mashed potatoes, mixed with either cabbage or kale, and enriched with butter or cream. The name “Colcannon” is derived from the Gaelic term “cal ceannann,” which means “white-headed cabbage,” one of the key ingredients in the dish.

The preparation of Colcannon is straightforward, but the result is a dish that is both comforting and satisfying. The creamy potatoes are perfectly complemented by the slightly bitter greens, while the butter adds richness and depth of flavor. Often served as a side dish, Colcannon can also be a meal in itself, especially when paired with a piece of ham or bacon.

If you’re enjoying my work, consider checking out Eats History Shop for my e-cookbooks!

Colcannon

Ingredients

- 1 pound potatoes Yukon Gold or Russet

- 1/2 small head of cabbage or 2 cups of kale chopped

- 4 tablespoons butter

- 1/4 cup milk or cream

- 2 scallions finely chopped (optional)

- Salt and pepper to taste

Instructions

Cook the Potatoes:

- Peel and quarter the potatoes.

- Place them in a large pot of salted water and bring to a boil. Cook until tender, about 15-20 minutes.

Prepare the Cabbage/Kale:

- While the potatoes are cooking, melt 2 tablespoons of butter in a separate pan over medium heat.

- Add the chopped cabbage or kale and cook until wilted and tender, about 5-7 minutes.

Mash the Potatoes:

- Drain the cooked potatoes and return them to the pot.

- Add the remaining 2 tablespoons of butter and the milk or cream.

- Mash the potatoes until smooth and creamy.

Combine:

- Stir the cooked cabbage or kale into the mashed potatoes.

- Add the chopped scallions, if using, and season with salt and pepper to taste.

Serve:

- Serve the Colcannon hot, with a pat of butter melting on top, if desired.

- It pairs wonderfully with ham, bacon, or even on its own as a hearty meal.