During World War II (1939–1945), food shortages, supply chain disruptions, and rationing drastically changed the way people cooked and ate. Civilians and soldiers alike had to make do with limited ingredients, substitute foodstuffs, and innovative cooking techniques to stretch meals and ensure proper nutrition.

Each nation had its own rationing system, reflecting not only the war effort but also cultural and agricultural differences. In this post, we explore ten historically accurate wartime recipes, sourced from contemporary cookbooks, showcasing how different countries adapted their cuisine to the harsh realities of war.

Making Do and Carrying On: How WWII Rationing Transformed Cooking

World War II was not just fought on battlefields—it was fought in kitchens, markets, and homes as well. As war spread across Europe, the Pacific, and beyond, food shortages and disrupted supply chains forced nations to implement strict rationing policies to ensure that both civilians and soldiers could be fed. The goal was clear: distribute available food fairly, prevent waste, and sustain populations under extreme circumstances. Governments issued ration books, limiting access to staple ingredients such as sugar, butter, meat, dairy, and eggs. This meant that households had to completely rethink how they cooked, learning to stretch ingredients further, use creative substitutes, and make the most of every scrap.

The impact of rationing was felt differently across the world. In Britain, rationing began in 1940 and remained in place for over a decade, shaping an entire generation’s relationship with food. The Ministry of Food launched extensive campaigns, encouraging people to grow their own vegetables in Victory Gardens, swap expensive meats for offal and lentils, and even make mock versions of favorite dishes, like “mock banana” from parsnips. In the United States, rationing arrived in 1942, and while food shortages were not as severe as in Europe, Americans were urged to cut back on luxury items like sugar and coffee to support the war effort. Citizens were encouraged to embrace “Victory Meat Extenders,” like soy and breadcrumbs, and learned to bake with alternative sweeteners like honey and molasses.

In Germany, rationing was more severe, as Allied blockades cut off supplies and food became increasingly scarce. Bread was often stretched with sawdust or potato flour, and ersatz products—substitutes for everything from coffee to butter—became the norm. The Soviet Union faced some of the worst hardships, with long breadlines, food rationing cards, and makeshift soups becoming the reality for millions. In Japan, rice became increasingly difficult to come by, leading to more reliance on preserved fish, seaweed, and foraged foods. The reliance on homegrown and locally available ingredients was universal, but the specifics of rationing varied greatly depending on each country’s resources, trade, and war conditions.

To help civilians adjust to these drastic changes, governments published ration cookbooks and distributed instructional pamphlets through newspapers and radio programs. These guides taught people how to prepare filling meals with minimal ingredients, preserve fresh produce through canning and pickling, and make nutritious meals without relying on traditional sources of protein or fats. Some of these wartime recipes, like Woolton Pie in Britain or Victory Bread in the U.S., were so widely used that they became cultural touchstones, remembered long after rationing had ended.

Ration cooking was not just about survival—it was also about morale. Meals were a crucial part of maintaining a sense of normalcy in a world upended by war. Even the simplest dish, carefully prepared and shared with family, could provide comfort during uncertain times. The ingenuity born out of necessity led to some surprisingly enduring culinary traditions, shaping food culture in ways that can still be seen today.

10 WW2 Ration Recipes from Different Nations

1. Woolton Pie (United Kingdom)

📜 Source: Ministry of Food, “The Kitchen Front” Cookbooks (1941)

When World War II broke out, Britain faced an urgent problem: how to feed its people while supplies were being cut off by German U-boats attacking merchant ships. With imports limited and food rationing in full effect by 1940, the British government had to ensure that civilians remained nourished without relying on traditional ingredients like meat, butter, and dairy. In response, Woolton Pie was introduced—a hearty, meatless dish named after Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food. The recipe, designed to be nutritious, filling, and easy to make with available rations, became a staple in British homes throughout the war.

Woolton Pie was made entirely from seasonal root vegetables, bulked up with oatmeal for thickness, and topped with a whole wheat crust made with margarine or lard instead of butter. The idea was to create a satisfying main meal that could sustain a family while using only ration-friendly ingredients. The Ministry of Food actively promoted this dish through radio broadcasts and pamphlets, encouraging citizens to incorporate vegetables from their own Victory Gardens. Though some found the dish bland, resourceful home cooks experimented with adding dried herbs, vegetable extracts like Marmite, or small amounts of cheese (if available) to enhance its flavor.

Ingredients:

- 2 potatoes, diced

- 2 carrots, diced

- 1 parsnip, diced (or substitute turnip)

- 1 leek, sliced (or use cabbage if leeks were unavailable)

- 1 onion, chopped

- ½ cup oatmeal (used as a thickener to create a stew-like consistency)

- 1 tsp vegetable extract (Marmite or Bovril) or a pinch of salt and pepper

- ½ cup water or vegetable stock (rationed, so sparingly used)

- 1 tsp dried thyme or parsley (optional, for flavor)

For the Pastry Crust:

- 1 ½ cups whole wheat flour

- 3 tbsp margarine, lard, or dripping (butter was rationed and rarely available for cooking)

- ½ tsp salt

- Cold water, as needed

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Vegetable Filling

- Peel and dice all vegetables into small chunks. The original Woolton Pie used whatever was available seasonally, so the combination of vegetables could vary.

- In a large saucepan, add the vegetables and just enough water or vegetable stock to cover them.

- Bring to a simmer and cook for 15–20 minutes, until the vegetables start to soften.

- Stir in the oatmeal and vegetable extract, and cook for another 5 minutes, allowing the mixture to thicken.

- Season with salt, pepper, and herbs if available.

- Pour the vegetable filling into a baking dish and set aside.

Step 2: Make the Pastry Crust

- In a large mixing bowl, combine the whole wheat flour and salt.

- Rub in the margarine or lard with your fingers until the mixture resembles coarse crumbs.

- Add cold water, one tablespoon at a time, mixing until a firm dough forms.

- Roll out the dough on a floured surface until it’s large enough to cover the baking dish.

Step 3: Assemble and Bake

- Lay the pastry over the vegetable filling, pressing the edges down to seal it. If desired, cut small vents in the crust to allow steam to escape.

- Bake in a preheated oven at 350°F (175°C) for 30–35 minutes, until the crust is golden brown.

- Allow to cool for 5 minutes before serving.

2. Victory Bread (United States)

📜 Source: “Victory Recipes” by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (1943)

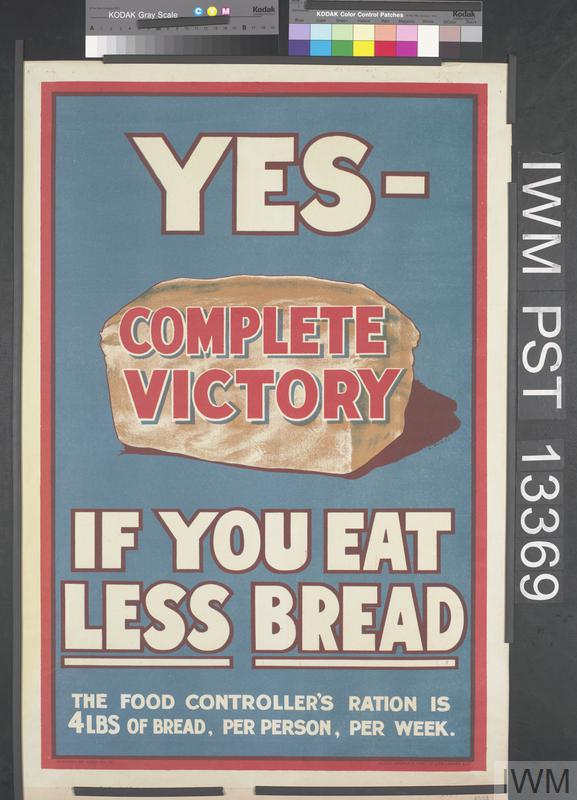

During World War II, wheat was a precious resource that needed to be conserved for soldiers and allies overseas. With the U.S. fighting a war on multiple fronts, the government launched rationing policies that limited sugar, butter, and white flour, encouraging home bakers to stretch their ingredients and find alternatives. Victory Bread became a staple in American households—a whole wheat, rye, or oat-based bread that used less refined flour and often incorporated alternative grains.

The U.S. Food Administration and War Rationing Board encouraged Americans to embrace this new type of bread as part of their patriotic duty. Posters, radio broadcasts, and cookbooks reminded people that “Food Will Win the War” and that baking Victory Bread was a way to support the troops while still feeding their families. The recipe was designed to be nutritious, filling, and flexible, allowing bakers to use whatever flour was available while reducing waste. Many versions also incorporated molasses or honey instead of sugar, as refined sugar was rationed.

This bread was not only a nutritional necessity but also a symbol of wartime unity, proving that small sacrifices on the home front could contribute to the larger war effort.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups whole wheat flour (a more nutritious alternative to white flour, which was reserved for soldiers)

- 1 cup rye or oat flour (helped conserve wheat supplies and added texture)

- 1 packet (2 ¼ tsp) dry yeast (commonly used in home baking)

- 1 cup warm water (essential for activating yeast)

- 1 tbsp honey or molasses (substituted for rationed sugar, adding depth of flavor)

- 1 tbsp vegetable oil, lard, or melted shortening (butter was limited, so alternatives were necessary)

- 1 tsp salt (for flavor and dough structure)

Instructions:

Step 1: Activate the Yeast

- In a small bowl, dissolve yeast in warm water (about 110°F/43°C).

- Add honey or molasses, stirring until dissolved.

- Let the mixture sit for 5–10 minutes, until it becomes frothy. This indicates that the yeast is active.

Step 2: Mix the Dough

- In a large bowl, combine whole wheat flour, rye (or oat) flour, and salt.

- Create a well in the center and pour in yeast mixture and vegetable oil.

- Stir until the dough begins to come together. If it is too dry, add 1–2 tbsp of warm water.

Step 3: Knead the Dough

- Transfer the dough to a lightly floured surface and knead for 8–10 minutes, until smooth and elastic.

- Place the dough in a lightly greased bowl, cover with a cloth, and let it rise in a warm place for 1 hour, or until doubled in size.

Step 4: Shape and Bake

- Once risen, punch down the dough and shape it into a loaf or small rolls.

- Place in a greased loaf pan or on a baking sheet, cover, and let rise for 30 minutes.

- Preheat oven to 375°F (190°C).

- Bake for 30–35 minutes, or until golden brown and sounds hollow when tapped on the bottom.

- Let cool before slicing.

3. Ersatz Coffee (Germany)

📜 Source: German Homefront Cooking Guides (1942), “Reichskochbuch” (1941)

By the early 1940s, Germany was facing severe shortages due to Allied blockades and war rationing policies. Among the first luxuries to disappear was coffee, an imported commodity that quickly became scarce as international trade routes were cut off. For many Germans, the morning cup of coffee was a deeply ingrained ritual, and the loss of real coffee beans meant the rise of Ersatzkaffee, or substitute coffee.

Ersatz coffee was not new—it had been used during previous wars and economic crises—but during World War II, it became a daily necessity for civilians and soldiers alike. Instead of coffee beans, the German home front relied on locally available, roasted ingredients such as barley, chicory root, acorns, rye, dandelion roots, and even beets. These substitutes provided a dark, bitter brew that resembled coffee, though it lacked caffeine.

The government encouraged Ersatz coffee as part of the “Kriegsküche” (War Kitchen) movement, promoting self-sufficiency and the use of alternative food sources. Housewives followed ration book recipes to make their own versions, and pre-made Ersatzkaffee blends were sold in stores. While not as rich or stimulating as real coffee, this beverage provided a sense of normalcy and became a symbol of German endurance during the war.

Ingredients:

- 1 cup roasted barley or chicory root

- 3 cups water

Instructions:

- Roast barley or chicory until dark brown.

- Grind finely and brew like regular coffee.

- Strain and serve.

- Sweeten with rationed sugar or honey if available.

4. Rice and Sardine Onigiri (Japan)

📜 Source: Imperial Army Ration Manuals (1944)

During World War II, Japan faced severe food shortages due to limited agricultural land, a naval blockade, and the prioritization of resources for the military. Rice, the backbone of Japanese cuisine, was heavily rationed and supplemented with millet, barley, and sweet potatoes to stretch supplies. Fresh fish became increasingly rare, as Japan’s fishing industry was impacted by the war, leading civilians and soldiers alike to rely on preserved fish, such as canned sardines, dried anchovies, or fermented seafood.

One of the simplest and most sustaining meals available during wartime was onigiri, or rice balls—a portable, compact, and nutrient-dense dish that could be easily carried and eaten without utensils. For civilians, onigiri made with minimal rice and preserved fillings became a daily necessity. In contrast, soldiers in the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy often received dried or pickled onigiri in their rations, sometimes accompanied by miso soup or seaweed when available.

Sardine onigiri was one of the most practical and protein-rich variations, making use of canned sardines, soy sauce, and limited seasonings to create a filling meal. While modern onigiri can be wrapped in nori (seaweed), wartime versions often omitted this due to shortages of dried seaweed, relying instead on a salted rice exterior to preserve freshness.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups cooked rice (or a mix of rice and barley to stretch rations)

- 1 small canned sardine, mashed (preserved fish was used in place of fresh seafood)

- 1 tsp soy sauce or miso paste (rationed, but still available in small quantities)

- *1 tbsp sesame seeds or finely chopped pickled radish (if available, for flavor and texture)

- ½ tsp salt (used to season the rice and aid preservation)

- Optional: small strip of dried seaweed (nori), if available

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Filling

- Drain the canned sardine, removing excess oil or brine.

- Mash the sardine with a fork and mix with soy sauce or miso paste to enhance flavor.

- Add sesame seeds or finely chopped pickled radish, if available, for extra texture.

Step 2: Shape the Onigiri

- Wet your hands lightly and rub them with a pinch of salt to help preserve the rice and prevent sticking.

- Take a small handful of warm rice and flatten it in your palm.

- Place a teaspoon of the sardine mixture in the center of the rice.

- Carefully fold the rice over the filling, pressing gently to form a compact triangle or round ball.

Step 3: Wrap and Store

- If available, wrap with a small strip of dried seaweed (nori) for extra flavor.

- If seaweed was not available, the salted rice exterior helped keep the onigiri fresh longer.

- Onigiri could be eaten immediately or wrapped in cloth or leaves for soldiers and workers to carry with them.

5. Borscht (Soviet Union)

📜 Source: Soviet Wartime Cookbook (1942)

By the time World War II reached the Soviet Union, the country faced one of the harshest food shortages of any major power. With the Nazi invasion in 1941, agricultural lands were destroyed, supply lines were cut, and the Soviet people endured severe rationing, famines, and extreme cold. While urban populations in cities like Moscow and Leningrad relied on strict government-issued rations, rural villagers made do with whatever they could forage, grow, or trade.

Borscht, a beet-based soup that originated in Eastern Europe, became a crucial survival dish for both civilians and soldiers. Its nutrient-dense ingredients, long shelf life, and adaptability made it a staple throughout the war. In times of scarcity, families would stretch it with cabbage, potatoes, or even just water and salt, ensuring that everyone had something warm and filling to eat. Soldiers on the front lines also received borscht in their military rations, often in dehydrated or canned form, where they could reconstitute it by adding water and boiling it over an open flame.

Though pre-war versions of borscht included meat, sour cream, and garlic, the wartime adaptations relied more heavily on beets, cabbage, and potatoes, reflecting the struggles of Soviet food shortages. It was a dish that embodied resilience, warmth, and sustenance, helping the Soviet people endure some of the most brutal conditions of the war.

Ingredients:

- 2 beets, shredded (provides color, flavor, and essential nutrients)

- 1 potato, diced (adds bulk and energy, replacing scarce grains)

- ½ small cabbage, shredded (a wartime staple that was easy to grow in Victory Gardens)

- 1 small onion, chopped (rationed, but commonly used for flavor)

- 4 cups water or weak vegetable broth (meat broths were often unavailable)

- 1 tbsp tomato paste or crushed tomatoes (if available, for extra richness and acidity)

- ½ tsp salt (to enhance flavor, as spices were rare)

- 1 tbsp sunflower oil or lard (for sautéing; oil was rationed but still used in small amounts)

- 1 tsp vinegar or pickled beet juice (to bring out the tartness in place of sour cream, which was scarce)

Optional Garnishes (if available):

- Dollop of sour cream or kefir (pre-war versions included this, but it was rare during rationing)

- Chopped fresh dill or parsley (for extra flavor, if available in home gardens)

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Vegetables

- Peel and shred the beets, keeping them separate to preserve their deep red color.

- Chop the onion, potatoes, and cabbage into small pieces.

Step 2: Cook the Base

- In a large saucepan or pot, heat 1 tbsp of sunflower oil or lard over medium heat.

- Sauté the onion until translucent, about 3 minutes.

- Add shredded beets and tomato paste, cooking for another 5 minutes to release their sweetness.

Step 3: Simmer the Soup

- Pour in water or weak vegetable broth and bring to a boil.

- Add potatoes and cabbage, reducing the heat to a simmer.

- Stir in vinegar or pickled beet juice to help maintain the vibrant color.

- Let the soup cook for 30–40 minutes, until the vegetables are tender.

- Season with salt to taste.

Step 4: Serve and Enjoy

- Ladle into bowls and garnish with fresh dill or a small dollop of sour cream, if available.

- Serve hot, ideally with a piece of rationed black bread or a simple wheat cracker.

Ingredients:

- 2 beets, shredded

- 1 potato, diced

- ½ cabbage, chopped

- 1 onion, chopped

- 4 cups water

- Salt and vinegar to taste

Instructions:

- Boil all ingredients together until tender.

- Add salt and vinegar for flavor.

- Serve with black bread if available.

6. German Potato Pancakes (Kartoffelpuffer) (Germany)

📜 Source: German Homefront Cookbook, “Reichskochbuch” (1942)

As World War II dragged on, Germany faced increasing shortages due to Allied blockades, the prioritization of food for the military, and the devastation of agricultural lands. Basic food items, including meat, dairy, and wheat, became luxuries, and German households had to rely on rationing and substitute ingredients to prepare daily meals.

Potatoes became a crucial survival food during the war, providing a cheap, calorie-dense, and versatile base for many dishes. Kartoffelpuffer, or German potato pancakes, became a widely eaten wartime meal because they required only a few simple ingredients, most of which were still relatively accessible through rationing. These crispy pancakes were often served plain, with applesauce, or with a thin spread of margarine, as butter and sugar were in extremely short supply.

Kartoffelpuffer were especially popular among civilians, factory workers, and children, as they could be made quickly and stretched with additional starches like flour or breadcrumbs. Soldiers on the front lines also encountered variations of this dish, as military field kitchens often used potatoes to bulk up rations. Despite the hardship, Kartoffelpuffer remained a comforting and familiar meal, providing warmth and sustenance during one of Germany’s most challenging periods.

Ingredients:

- 3 medium potatoes, grated (potatoes were not rationed and were one of Germany’s most widely available foods)

- 1 small onion, grated (added for flavor, when available)

- 2 tbsp flour or breadcrumbs (to help bind the mixture, depending on ration supplies)

- ½ tsp salt (for seasoning; salt was still commonly available during the war)

- ¼ tsp black pepper (if available; spices were limited and often expensive)

- 1 egg (or 1 tbsp reconstituted powdered egg) (eggs were rationed, so many used powdered substitutes)

- 2 tbsp vegetable oil, lard, or rendered fat (cooking oil was heavily rationed, so leftover fats were commonly used)

Optional Accompaniments:

- Applesauce (Apfelmus), if available (sugar was rationed, so many households preserved apples without added sugar)

- Thin spread of margarine or a drizzle of beet syrup (for extra calories in an otherwise lean meal)

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Potatoes

- Peel and grate the potatoes and onion into a bowl.

- Using a cloth or your hands, squeeze out excess liquid from the potatoes to prevent sogginess.

Step 2: Mix the Batter

- In a bowl, combine grated potatoes, onion, flour (or breadcrumbs), salt, pepper, and egg substitute.

- Stir until a thick batter forms, making sure everything is well coated.

Step 3: Fry the Kartoffelpuffer

- Heat 1 tbsp of oil or rendered fat in a pan over medium heat.

- Scoop a small handful of the batter and flatten it into a thin pancake in the pan.

- Fry each side for 3–4 minutes, until golden brown and crispy.

- Repeat for the remaining batter, adding oil sparingly as needed.

Step 4: Serve and Enjoy

- Serve plain or with applesauce if available. In many cases, the pancakes were eaten on their own as a main meal, especially when meat or dairy was unavailable.

7. Oatmeal Brown Betty (United States)

📜 Source: “Victory Recipes” by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (1943), “The Victory Binding of the American Woman’s Cook Book” (1942)

During World War II, the U.S. government placed strict rationing on sugar, butter, and white flour, making traditional desserts difficult to prepare. With the war effort demanding vast amounts of resources, families on the home front had to improvise and adapt their recipes. Oatmeal Brown Betty was one such adaptation—a dessert that made use of stale bread, ration-friendly oats, naturally sweet apples, and alternative sweeteners like molasses or honey.

This simple baked dessert was an excellent way to avoid food waste while still providing a comforting, homemade treat. Unlike traditional pies and cakes, which required precious sugar, butter, and eggs, Brown Betty could be made with readily available ingredients, making it one of the most common wartime desserts in American households. Many variations of this dish existed before the war, but during rationing, homemakers relied on oats and fruit to replace missing ingredients.

The government actively encouraged recipes like Brown Betty in rationing cookbooks and home economics classes, emphasizing that making do with available supplies was a patriotic duty. While it may have lacked the richness of pre-war desserts, it provided a warm, spiced, and nostalgic taste of home, offering comfort to families whose loved ones were serving overseas.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups stale bread, crumbled (a key rationing practice was avoiding food waste, so stale bread was repurposed)

- 1 cup rolled oats (provided texture and replaced some of the flour in traditional recipes)

- 4 apples, peeled and sliced (apples were among the more readily available fruits)

- ¼ cup honey or molasses (sugar was heavily rationed, so alternatives were used)

- 1 tsp cinnamon (a widely used spice that added warmth to simple dishes)

- 1 tbsp margarine or vegetable shortening (butter was rationed, so alternatives were necessary)

- ½ cup water or weak tea (used to keep the dish moist without relying on dairy)

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Base

- Preheat oven to 350°F (175°C).

- Grease a small baking dish lightly with margarine or shortening.

Step 2: Layer the Ingredients

- Spread half the sliced apples in the bottom of the dish.

- Sprinkle with half the crumbled bread and oats.

- Drizzle with half the honey or molasses and a pinch of cinnamon.

- Repeat the layering process, finishing with a final sprinkle of oats and bread on top.

Step 3: Bake the Dessert

- Pour ½ cup of water or weak tea over the dish to keep it moist.

- Dot the top with small bits of margarine or shortening for added richness.

- Bake for 30–35 minutes, until the top is golden brown and the apples are soft.

Step 4: Serve and Enjoy

- Allow to cool slightly before serving. If available, a small drizzle of evaporated milk could be added for extra flavor.

8. Wartime Meatloaf (United Kingdom & United States)

📜 Source: Ministry of Food, “The Ration Book Diet” (1943), U.S. War Ration Cookbook (1943)

During World War II, meat was one of the most heavily rationed food items in both the United Kingdom and the United States. With much of the available beef, pork, and poultry being diverted to soldiers, civilians had to find creative ways to stretch their meat supply. In both countries, meatloaf became a staple wartime dish, using fillers such as lentils, bread crumbs, oatmeal, or vegetables to extend a small portion of ground meat into a full meal.

Governments actively promoted meat extenders, encouraging families to make their rations last as long as possible while still maintaining proper nutrition. Recipes for Victory Meatloaf or Wartime Meatloaf often appeared in rationing pamphlets, home economics classes, and government-issued cookbooks, teaching homemakers how to make flavorful and hearty meals despite shortages.

This version of wartime meatloaf, commonly prepared in both Britain and America, includes grated vegetables and breadcrumbs to stretch the meat, along with Worcestershire sauce or mustard powder for added depth, since expensive seasonings were often unavailable.

Ingredients:

- ½ lb minced beef or corned beef substitute (meat was rationed, so smaller portions were common)

- ½ cup cooked lentils or mashed beans (helped bulk up the loaf and added protein)

- 1 small onion, finely chopped (added flavor without using costly seasonings)

- 1 carrot, grated (common wartime filler that added moisture and texture)

- ½ cup stale breadcrumbs or rolled oats (helped bind the meat and make it more filling)

- 1 tbsp Worcestershire sauce or mustard powder (optional, for flavor if available)

- 1 egg or 1 tbsp reconstituted powdered egg (helped bind the loaf together)

- ½ tsp salt (for seasoning, as salt was still accessible but limited)

- ¼ tsp black pepper or dried herbs (optional, if available)

- 1 tbsp vegetable oil, margarine, or drippings (for greasing the pan and keeping the loaf moist)

Optional Topping (if available):

- 1 tbsp rationed ketchup or watered-down tomato paste (provided extra flavor and moisture)

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Mixture

- Preheat oven to 350°F (175°C).

- In a large bowl, combine minced beef (or corned beef substitute), lentils (or mashed beans), chopped onion, grated carrot, and breadcrumbs (or oats).

- Stir in Worcestershire sauce (if available), salt, pepper, and dried herbs.

- Beat egg (or powdered egg substitute) and mix it into the ingredients to help bind everything together.

Step 2: Shape the Meatloaf

- Grease a small loaf pan or shape the mixture into a loaf on a greased baking tray.

- If available, spread a thin layer of ketchup or tomato paste on top for extra moisture and flavor.

Step 3: Bake the Meatloaf

- Place in the oven and bake for 45 minutes to 1 hour, or until firm and browned on top.

- If necessary, baste the meatloaf with a little water or broth halfway through baking to keep it moist.

Step 4: Serve and Enjoy

- Allow the meatloaf to cool slightly before slicing.

- Serve with boiled potatoes, steamed vegetables, or a thick gravy made from flour and drippings.

9. German Wartime Barley Soup (Gerstensuppe)

📜 Source: German Homefront Cookbook, “Reichskochbuch” (1942), German Rationing Guidelines

As food shortages intensified in Nazi Germany, rationing became increasingly strict, and families had to rely on staple ingredients that were affordable, nourishing, and easy to store. Barley, a grain that had long been a part of German and Central European diets, became a wartime necessity as wheat was reserved for the military, and meat became a luxury.

Gerstensuppe, or barley soup, was a simple yet filling dish that could be made with minimal ingredients, allowing families to stretch their rations while still providing warmth and nutrition. It was particularly popular among low-income households, factory workers, and soldiers’ families, who had to rely on basic grains, root vegetables, and foraged herbs to sustain themselves.

While pre-war versions of this soup often included bacon, sausages, or beef bones, the wartime adaptation had to be made meatless or with only a small amount of preserved meat. Instead, cooks relied on barley, potatoes, carrots, and whatever vegetables were available. This dish was commonly eaten in households, schools, and public kitchens, as well as distributed as part of community soup kitchens set up by the German government to feed struggling families.

Ingredients:

- ½ cup pearl barley (a staple grain that replaced wheat in many wartime recipes)

- 1 large potato, diced (provided bulk and energy, making the soup more filling)

- 1 carrot, diced (added vitamins and flavor, commonly grown in home gardens)

- 1 small onion, chopped (rationed but still widely used for flavor)

- 4 cups vegetable broth or water (meat broths were rare, so vegetable-based versions became common)

- ½ tsp salt (for seasoning; salt was still accessible but rationed)

- ¼ tsp black pepper or dried thyme (if available, added for extra depth of flavor)

- 1 tbsp vegetable oil, lard, or margarine (used to sauté the vegetables; cooking fats were strictly rationed)

Optional Additions (if available):

- A small piece of smoked sausage or bacon (used sparingly if a family had access to rationed meat)

- Chopped cabbage or turnip greens (for extra nutrients and fiber)

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Ingredients

- Rinse the barley thoroughly under cold water to remove excess starch.

- Chop the potatoes, carrots, and onion into small, bite-sized pieces.

Step 2: Sauté the Vegetables

- In a large pot, heat 1 tbsp of vegetable oil, margarine, or lard over medium heat.

- Add the onion and sauté for 2–3 minutes until translucent.

- Add the carrots and potatoes, stirring for another 2 minutes to coat them in the oil.

Step 3: Cook the Soup

- Add the rinsed barley and stir well.

- Pour in 4 cups of vegetable broth or water and bring to a boil.

- Reduce the heat and let the soup simmer for 40–45 minutes, stirring occasionally until the barley is tender.

Step 4: Season and Serve

- Season with salt, pepper, and dried thyme (if available).

- If using rationed meat (such as a small piece of smoked sausage or bacon), add it in the last 10 minutes to release its flavor.

- Serve hot, ideally with a slice of dark rye bread, if available.

10. Wartime Apple Crumble: A Sweet Victory on the Home Front

📜 Source: “Victory Recipes” by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (1943), “The Victory Binding of the American Woman’s Cook Book” (1942)

During World War II, sugar, butter, and white flour were strictly rationed in the United States, making traditional pies and cakes difficult to prepare. However, American homemakers found creative ways to continue baking comforting desserts while stretching their supplies. Apple Crumble, a simplified version of apple pie, became a popular wartime treat, as it used oats, honey, and margarine instead of sugar, butter, and refined flour.

Apples were a widely available and inexpensive fruit, often grown in Victory Gardens or sourced from local farms. Unlike pies, which required precious butter for a flaky crust, crumbles could be made with less fat and bulked up with rolled oats or breadcrumbs, making them a more ration-friendly alternative. Homemakers could serve this dish as a morale-boosting dessert for their families, providing a small taste of normalcy during uncertain times.

While pre-war versions of apple crumble included generous amounts of sugar, spices, and butter, the wartime adaptation relied on natural sweetness from fruit, small amounts of molasses or honey, and a simple oat-based topping. The result was a humble yet delicious dessert that remains a staple of American baking today.

Ingredients:

For the Apple Filling:

- 4 medium apples, peeled and sliced (apples were among the most accessible fruits during rationing)

- 2 tbsp honey or molasses (substituted for sugar, which was strictly limited)

- 1 tsp cinnamon or nutmeg (if available, added for flavor without using excess sugar)

- ½ tsp salt (enhanced the natural sweetness of the apples)

- 1 tbsp cornstarch or flour (helped thicken the filling using minimal ingredients)

- ½ cup water or weak tea (used instead of fruit juice, which was expensive and hard to find)

For the Crumble Topping:

- ¾ cup rolled oats or stale breadcrumbs (replaced much of the flour in traditional crumbles)

- ½ cup whole wheat flour (white flour was prioritized for troops, so whole wheat was more commonly used at home)

- 2 tbsp margarine, lard, or vegetable shortening (butter was heavily rationed and rarely used in everyday baking)

- 1 tbsp honey or molasses (to help bind the topping together)

Instructions:

Step 1: Prepare the Apple Filling

- Preheat oven to 350°F (175°C).

- Peel and slice the apples into thin wedges.

- In a mixing bowl, toss the apples with honey (or molasses), cinnamon, salt, and cornstarch (or flour).

- Pour ½ cup of water or weak tea over the apples to help create a syrupy texture while baking.

- Spread the apples evenly in a greased baking dish.

Step 2: Make the Crumble Topping

- In a separate bowl, mix rolled oats (or breadcrumbs), whole wheat flour, and margarine (or shortening).

- Add honey or molasses, stirring until the mixture becomes crumbly.

- Sprinkle the crumble mixture evenly over the apples.

Step 3: Bake and Serve

- Bake for 30–35 minutes, until the topping is golden brown and crisp.

- Let cool for a few minutes before serving. If available, serve with a small drizzle of evaporated milk or reconstituted powdered milk for added richness.

From Scarcity to Resilience: The Legacy of Wartime Cooking

World War II was a time of great hardship, but it was also an era of ingenuity, adaptability, and perseverance—especially in the kitchen. The rationing policies that shaped wartime cooking forced families around the world to make do with less, stretch ingredients further, and find creative ways to prepare meals with limited resources. From Woolton Pie in Britain to Ersatz Coffee in Germany, from Borscht in the Soviet Union to Victory Bread in the United States, these dishes tell the story of how ordinary people faced extraordinary challenges and refused to let scarcity define their daily lives.

Beyond simply providing sustenance, these meals became symbols of resilience and unity. They connected families, strengthened communities, and reminded people that even in the darkest of times, a warm meal could provide comfort and hope. Government campaigns encouraged not just conservation, but a sense of shared responsibility, reminding civilians that their sacrifices on the home front were just as crucial as the battles fought abroad.

The impact of wartime cooking did not disappear when the war ended. Many of these recipes continued to influence post-war food culture, with some, like Apple Crumble and Meatloaf, remaining beloved comfort foods to this day. Others, like Ersatz Coffee and wheat-stretched bread, faded as people eagerly returned to pre-war abundance. However, the lessons learned—reducing waste, valuing homegrown ingredients, and making thoughtful use of every rationed item—remain relevant even in modern times.

In revisiting these historical recipes, we not only honor the resilience of those who endured the war but also gain a deeper appreciation for the food we have today. Wartime cooking was never just about survival—it was about creativity, endurance, and the enduring human spirit that turns even the simplest meal into an act of hope.